Localization and Exoticism of Otome Games

Since the 1990’s onwards, the interest in Japanese media has grown exponentially and dramatically. I don’t need to explain how successful anime and manga are around the world; with their willingness to delve into complex and dark storylines, plays on universal themes, and uniquely Japanese character tropes- anime and manga simply resonate with audiences around the world. Here in America, we have communities of individuals all across the country who actively engage in anime/manga media whether through fan clubs, conventions, or digital forums. The popularity of Japanese mobile games, Otome or otherwise, is directly linked to how sensationalized other forms of Japanese media (anime and manga) have become abroad. Mio Consalvo, who cites the father of convergence media and fandom studies: Henry Jenkins, says “....convergence means more than technologies or content coming together in one box. It instead alludes to the convergence of content across media platforms, and the joining together of media producers and consumers in the production and negotiation of that content—through user-generated content, greater feedback mechanisms for consumers, or fan-driven media campaigns.” I’d argue here that the progression of anime and manga to video games (or vice versa) was a fan-pushed, consumer-led decision for Japanese media corporations.

From manga to anime to video games and mobile games, Japan has tapped into, exploited, and maximized its pop culture commodities. Video games, and mobile games, are just another extension of storytelling on another platform. At the heart of storytelling, is the ability to express culture whether through literary, symbolic, or metaphorical means. I picked this topic because I was fascinated with the idea that video games can share culture and tell stories the same as anime and manga. I’m not a video game enthusiast, but I find this platform’s ability to tell stories in a way that is immersive and interactive to be extremely fascinating. It might be an exaggeration to say so, but I feel that since the invention of television, we have been moving towards more and more interactive ways to experience storytelling. We developed 3D films, D-box seats in theaters that are supposed to vibrate and move with the sound effects, and virtual reality devices we can strap our phones onto and become immersed with. Consalvo once again quotes Jenkin’s work saying, “‘each media manifestation makes a distinct but interrelated contribution to the [sic] unfolding of a narrative universe.’” I think the narrative universe of Japanese Otome games is something worth examining. I picked Otome games mostly for personal reasons, but also because this game style is inherently narrative in nature.

Otome games have only recently started gaining popularity in the global market. An otome game is a romance/dating video game that is typically made for a female audience. Players “play” the role of the protagonist in a storyline that interacts with other male characters and potential romantic partners. The storylines and paths the protagonist can take are predetermined, but the player has the ability to choose their potential romantic partner, and with prompted responses, can develop their protagonist’s personality. Otome games are broken into chapters, often there is a time contingency placed before a player can move from one chapter to another. As the player interacts with the characters, the story progresses.

Despite the relative popularity of Otome games in Japan, the inevitable growth conundrum that all popular media corporations face when they are trying to increase their profit margins, is the limited domestic market. Consalvo attributes Japan’s “graying population” to one of the causes for Japan pushing its media outward and to more global audiences. This refers to Japan’s declining birthrate and the lack of youths, who are the primary target for mobile games. In an effort to gain overseas audiences, media corporations have to slightly tweak their products to suit the tastes of a global audience. This “tweaking” is done intentionally, and thoughtfully so that it appeals to a global audience but also stays true to Japanese culture.

Ikemen Sengoku and Princess to Be are two such otome games. Both games were designed and distributed to a global audience. The visions of the media companies, Cybird and DeareaD Inc. respectively, have very different corporate philosophies. My analysis will show how these two games differ, how much each game reveals about Japanese culture, and in what ways these games were modified to suit an international audience.

Ikemen Sengoku

Ikemen Sengoku is a historical romance games; the character cast are real warlords who have lived through the Sengoku Era and Oda Nobunaga is the man that nearly united all of Japan under one rule. From the art, to the setting, the characters and the music, everything about this game is deeply imbued in Japanese culture; and with a premise like falling into the Sengoku era, Japanese history as well. However, as you will see from my analysis of the female protagonist, this game is clearly oriented towards a Western (European/North American) audience.

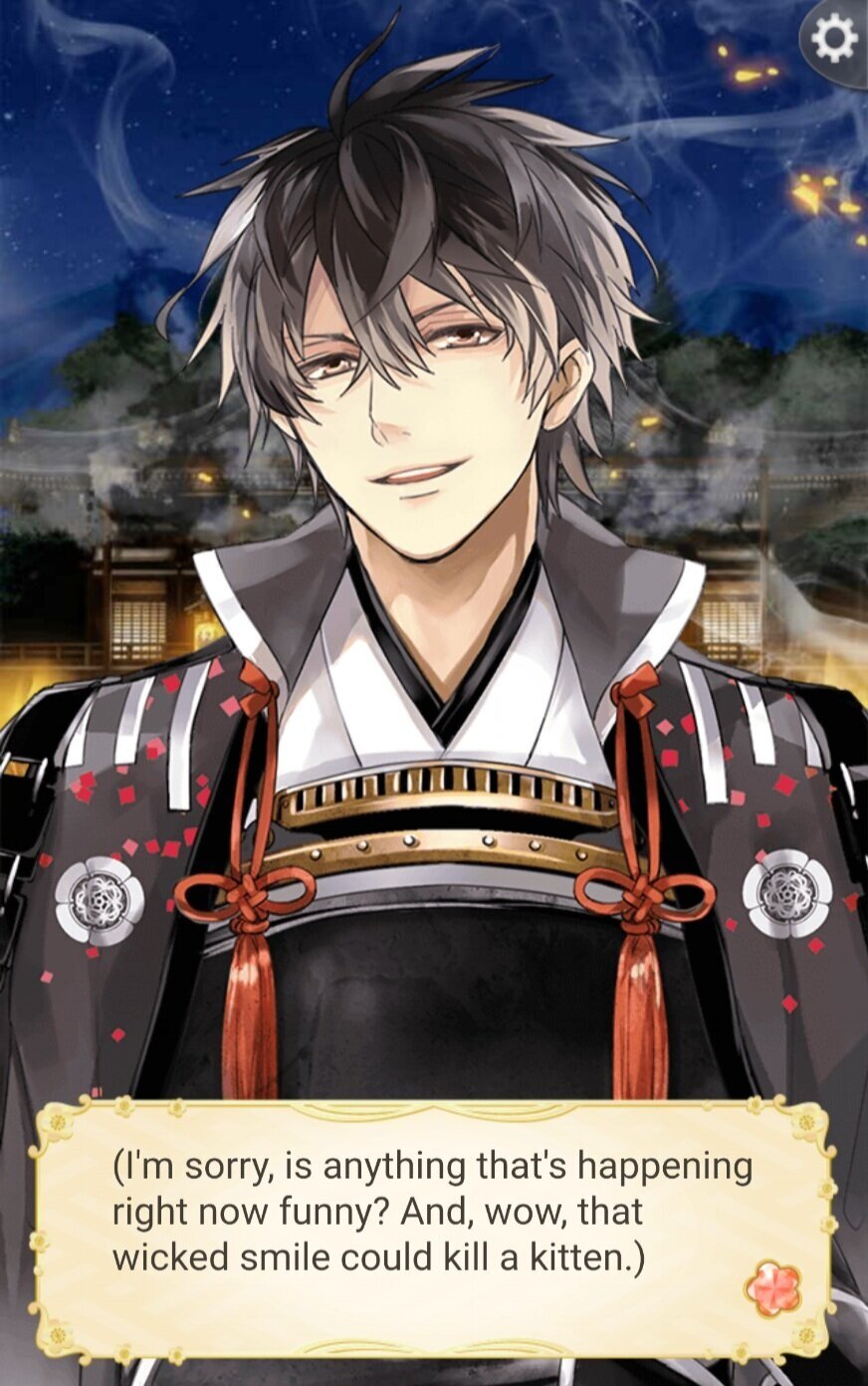

Cybirds corporate philosophies implicitly imply that their mission is to create an enjoyable gaming experience for all audiences, regardless of borders. In an interview, Yuki, staff member from Cybird, answered how the process of creating an Otome game for an American audience looked like. She stated that Cybird’s global games were originally Japanese, but undergo a localization process before being promoted abroad: “The biggest change that we make is the main character, the female. I like to compare it to Disney princesses. In the original Japanese game, the girl’s image was more like a damsel like the prince always has to protect the princess. But now if you watch newer Disney movies like Frozen, girls are much stronger. They have their own opinions and don’t rely on princes. So for American audiences, we change the character from having a shy, timid personality to one that’s more energetic and bold.” This has been true in my experiences with the game as well. The figure below shows the female protagonist reacting Sengoku making light of her for saying that she travelled back in time:

Her words are bold, full of sarcasm, and a rhetorical question. This attitude doesn’t align with hegemonic femininity in Japan which expects women to be chaste, innocent, and demure. As the Cybird staff indicated, the heroine is purposefully more bold in the American version than in the Japanese. This modification is known as localization. Localization is “the process of adapting a product or content to a specific locale or market” in order to make the target audience feel like the content is targeted for them. Localization transcends just translating content for global audiences; in Ikemen Sengoku this meant making a bolder, more independent female protagonist.In Ikemen Sengoku the players internal journey with characters and dialogue have been localized, but the external journey of the game invites players to understand Japanese culture. In the article, “Bringing Otome Games to the Other Side of the World,” the author comments on this topic, stating that cultural practices such as removing your shoes before entering the house, or the types of foods a character eats and the use of chopstick— these elements are not modified.

In Ikemen Sengoku the character’s clothing, setting, background music, use of pronouns (ore-sama and omae), the character’s treatment of women by that time period’s social norms, are all true to Japanese culture. These are elements that affect the player’s external journey of the story. The internal journey the players face has already been localized. This is a necessary “evil” Cybird must take to appeal to their audience. As Yuki mentioned earlier, the damsel-in-distress scenario doesn’t appeal to Western audiences as it does to Japanese audiences. In the article mentioned above, the author states, “‘Western audiences like to see a lead with an established personality, unlike the ones stereotyped in typical otome games,’ Chan said, going on to note that audiences for Purrfectly Ever After responded positively to their female lead Pastel being characterized as ‘a strong-willed, cat-turned-human girl who is a leader of a clan and a hero of justice.’ Even in the case of Amnesia, the most popular title among western audiences, the player is allowed to build a completely new personality for the protagonist following her memory loss.” This implies the western audiences expect more agency in the storytelling process— this emphasis on the actions of an individual is very much based on western philosophy. Global audiences will be able to empathize with the protagonist easier this way. Feeling empathetic towards the main avatar is a powerful tool- it allows users to become more immersed with the storytelling. Because the experience of the internal and external journey of Ikemen Sengoku diverge, the insight into Japanese culture is not entirely authentic. This is because Cybird’s purpose is more to entertain and create “happy moments” for all players and the difference in intentions reflects in the game’s design.

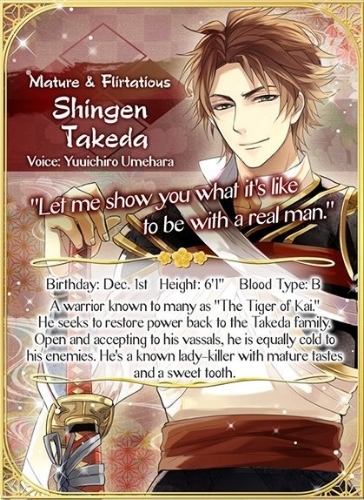

Another way in which localization can be seen is in the discrepancy between the English translation and Japanese dialogue. Shingen Takeda, one of our heroine’s candidates, is introduced as shown in the following image:

The Japanese dialogue here is: お出で. The literal translation of this is “come here.” The connotation in Japanese, however, is come closer, or come to me. The English translation reads as “Let me show you what it’s like to be with a real man.” This message does not come across in the Japanese dialogue. Yuki from Cybird states that one of the character archetypes in shoujo manga and otome games that Japanese audiences are already familiar with is the sadistic type. “we tend to tone down this aggressive nature in the American version. Sometimes the scenes might just seem too much to an American audience of stronger females, so that’s something we lessen in the Western version. In Japanese, the dialogue is not written as straightforward, but when translated into English, it can come off as too intense.” Shingen Takeda is not the sadistic type character, but similar to how aggressively a sadistic type character comes off, Shingen Takeda is suggestive and duplicitous in Japanese.

Rather than come across as intense, he comes off as passive and subtle. In an effort to localize the dialogue, the company has given a straightforward translation that introduces more information. “お出で” and “Let me show you what it’s like to be a real man,” send a very different message across to players. The explicit translation distances player from the subtlety and charm of the Japanese courtship and thereby from Japanese culture.

The purpose of Ikemen Sengoku is to engage with all audiences, regardless of cultures and borders. In that sense, this game does an excellent job of creating a welcoming protagonist, one that players can empathize with and experience this journey through the Sengoku era. However, because the game encourages players to understand Japanese culture from the outside looking in, it is difficult to say how authentic the experience will feel to players. Localization is an inherent force of encouraging otherness, however, if it is the otherness that attracts global audiences, it makes sense that Cybird would utilize this strategy to reach the widest possible audience.

Princess to Be

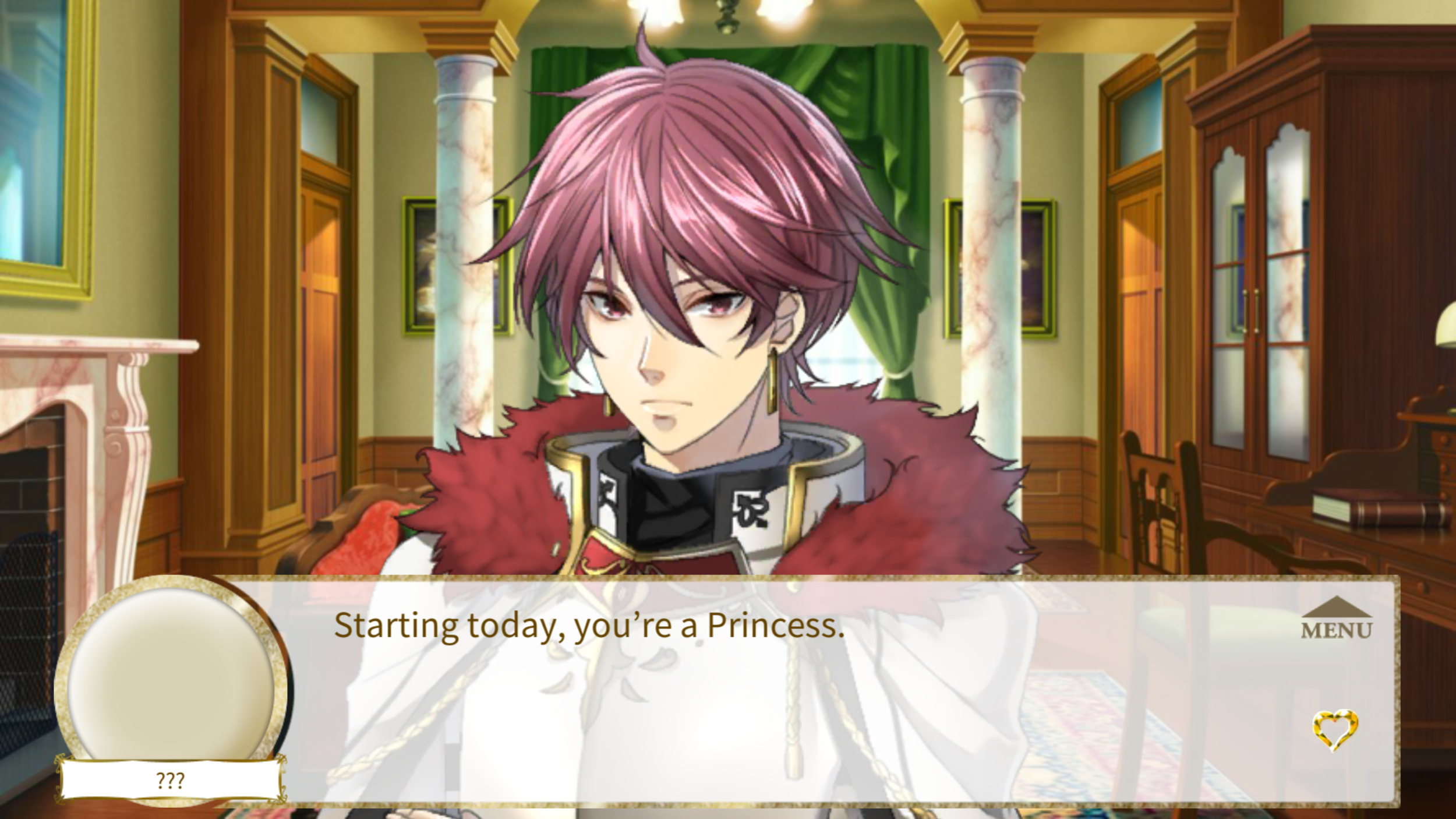

Princess to Be was released by DeareaD Inc, in 2017. The premise of the game is of a heroine, who resembles a runaway princess, being asked to be the princess’ double until the real princess is found. In the meantime, the heroine should not reveal that she is a fake. The story begins when Alec (red-haired character seen in the image below) brings the protagonist out of her isolated life in a mansion to the castle to replace the princess. The game is set in Victorian London and features a cast of a knight, a nobleman, and a prince. Princess to Be is also meant for an international audience, however, the company’s philosophy and approach to gameplay are inherently different than Cybird’s. DeareaD Inc’s corporate philosophy is “We will continue to work on creating a service to shake the hearts of otome as a company that provides two-dimensional content representing Japan.”

Unlike Ikemen Sengoku, in which the storyline and premise are inherently Japanese, Princess to Be is set in the Victorian Era. Neither the setting, the characters nor the music give the impression that this game was produced by a Japanese company, aside from the manga art style. However, DeareaD Inc,’s goal is to share content that represents Japan and they achieve representing Japanese values through their the female protagonist.

Unlike the protagonist of Ikemen Sengoku, there appears to be little to no attempt of localizing the characters and dialogue of Princess to Be. In Figure 6 below, you can see that the practice of bowing as a greeting or closing is present when the characters interact. While the protagonist of Ikemen Sengoku took on a sardonic and defiant approach to facing Nobunaga, this protagonist’s interactions with other characters reflect Japan’s culture of respect and showing seniority. Even more interesting, is that the female protagonist responds with a deeper bow than the male character. This reinforces the stereotypical gender roles that expect women to be kind, demure, and graceful.

In another instance, the female protagonists reveals that she’s spent her entire life cut off from the outside world, and until male character came to take her away to be the fake princess, her life was sedentary. In Japan, child-rearing and being a housewife is a respectable position, it represents women as both caretakers and managers of the families well-being. The more well off the family is, the better it reflects on the woman The first line references how the idea of a woman staying at home is not something that is not uncommon or out of place, and how this protagonist was living vicariously through books. It paints this gender role, not in a positive light, but as an axiom. Almost ironically, this is followed by the Japanese philosophy the men and women should work for the betterment of society. The second line reiterates the idea of being devoted to working. Both of these philosophies are highly gendered and are stereotypical expectations of women, but Princess to Be does accomplish introducing gender roles that women in Japan experience.

In Ikemen Sengoku, the protagonist is a well-developed character with both an internal and external journey through the story. In Princess to Be the protagonist's journey is almost entirely external. Figure 8 below shows Alec’s introduction: the character who propels the journey of the game. Until Alec brings the protagonist out of her isolated lifestyle, she doesn’t have much connection to the “outside world.” Upon meeting her, Alec tells her: “Starting today, you are the princess.” This is shown below. The protagonist doesn’t have much agency in the start of the game, her path is predestined for her and she willingly tags along.

The sequence of images below shows how conversation taking place leading up to the protagonist accepting the role of a fake princess. Although this character is asking her politely, contextually the game reveals how little choice she has to say anything but yes. This part of the game is pre-written without an option for the protagonist to reject the request.

This lack of agency might be uncomfortable to Western audiences who are more familiar with the bold protagonist of Ikemen Sengoku, but the intent is not to strip the female protagonist of agency. In romance media, it is common for the protagonist to be an “invisible heroine.” A blogger by the name Lijakaca summarizes Jill Astly’s presentation from the 2010 Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association Conference to explain the purpose of an invisible heroine is in the Otome gaming world: “Because the game is intended to have some effect on the player’s emotions, games usually try to make the player feel as if they are the heroine, rather than simply watching a movie and following along. To do this, the heroine rarely has an avatar that shows up onscreen the same way as the other characters.” DeareaD Inc. utilizes this method because it is one that Japanese audiences are familiar with and by incorporating it in their globalized Princess to Be, global audiences are experiencing gameplay the same way Japanese audiences do. So while Ikemen Sengoku has a bold and independent protagonist that players can connect to, Princess to Be’s protagonist purposefully made invisible so that the player can focus on the other characters: the external journey.

The purpose of Princess to Be was to represent Japan. Many of the features of this game are created with the tastes and needs of a Japanese audience and their experiences with Otome gameplay in mind. In this way, global audiences can experience the gameplay the same as Japanese players. In spite of the lack of Japanese cultural elements in the setting of the story, the female protagonist, the characters, and their interactions all convey Japanese values.

Conclusion

The globalization of a product is a delicate process the relies entirely on the intentions of the company behind it. Ikemen Sengoku had an inherently Japanese plot and characters, yet the protagonist revealed how much of the game had been localized to suit the needs of a western audience. Despite the lack of Japanese elements in the plot and characters, Princess to Be’s protagonist reveals inherently Japanese values. Both Cybird and DeareaD Inc, intended for their otome games to be for a global audience, yet their approaches to sharing their product, and by extension their culture, with global audiences is vastly different. It is difficult to say which of the two provides a more authentic experience to glimpsing at Japanese culture through otome games but both games succeed in the task of telling a story that global audiences can take part in.

References

Consalvo, Mia, “Convergence and Globalization of the Japanese Videogame Industry,” Cinema Journal (48), no. 3, 2009. Pg 133-141.https://muse.jhu.edu/article/266066

Ibid.

The growth conundrum is the need for a corporation to grow and generate a good level of profitability.

Thompson, John B. Merchants of Culture. 2010. Polity Press: Cambridge, UK.

Ibid, Mia Consalvo.

Top Message,” Cybird, 2018. http://www.cybird.co.jp/en/aboutus/#ceomessage.

Nguyen, Mai,“A Look into Cybird with an Otome Game Character.” asia pacific arts, August, 28, 2016,

http://asiapacificarts.usc.edu/w_apa/showarticle.aspx?articleID=20092&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

Kincaid, Chris, “A Look at Gendered Expectations in Japan,” Japan Powered, July 7, 2013. https://www.japanpowered.com/japan-culture/a-look-at-gender-expectations-in-japanese-society.

“What is Localization?” GALA: Globalization & Localization Association, last modified in 2018, https://www.gala-global.org/industry/intro-language-industry/what-localization.

Khalyleh, Hana, “Bringing Otome Games to the Other Side of the World,” Kill Screen, January 28, 2016,

https://killscreen.com/articles/bringing-otome-games-to-the-other-side-of-the-world/.

Ibid, Mai Nguyen

“About,” DeareaD, 2016, http://dearead.com/about?la=en.

Ibid, Chris Kincaid.

Ibid.

Lijakaca, “Romance Videogames- Selected Topics,” Lijakaca’s Otome Gaming Blog, Febrauary 22, 2013, http://lijaka.com/blog/2010/04/romance-videogames-selected-topics/